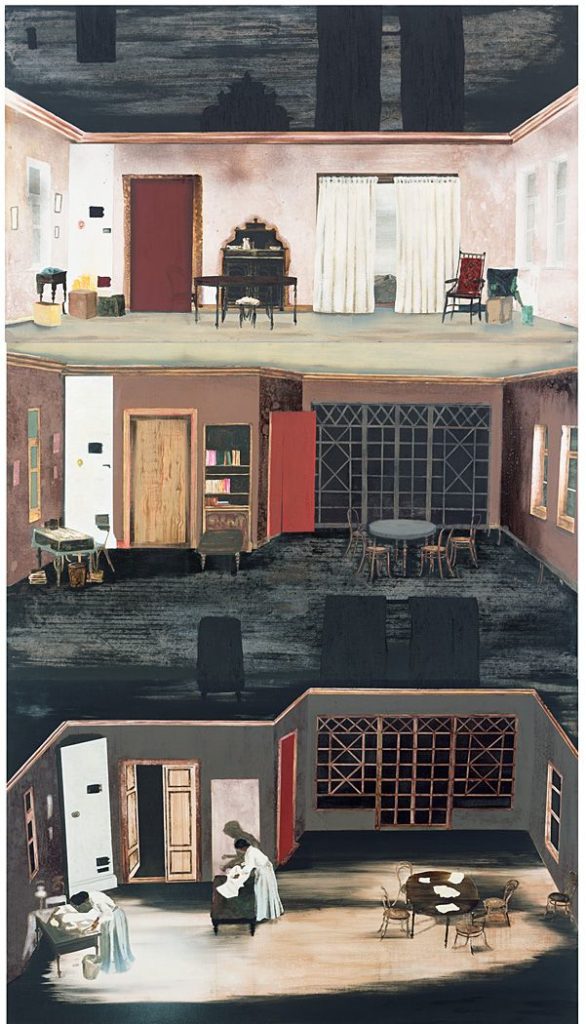

“Dollhouse”, Oil on panel in three parts, 229 x 122cm, courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery

One had to build shelters.

One had to make pockets and live inside them.

-Lorrie Moore, Like Life. Vintage, 1990

If home is sweet home, then why is the domestic sound terrifying? Horror stories are rooted around a home, or collection of homes we call a town. Countless artists have avoided direct representation of the home unless it’s a subversive attempt to expose the dark, inner sanctum of the familiar. Naturally artists remove sweetness from the domestic. Sweetness is heavy, and homes inspire escape.

Artists who are brave enough to dwell in the home with their work are generally female. A male artist rarely sits comfortably making work about the home, unless they are creating peeping versions of stereotypically, sexually-repressed suburban family vignettes verging on porn or extreme discomfort (e.g. Eric Fischl and Larry Sultan). Female artists also share a feeling of dread when it comes to the home. Louise Bourgeois had a life-long obsession with her childhood home. The trauma of her home life turned out literally in images of houses on human heads in her series Femme Maison (1946-47), and symbolically in some major installations such as “I Do, I Undo, I Redo” (2000) at the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall. In 2005 Kiki Smith created a masterful installation titled “Homespun Tales, Stories of Home Occupation” at the Fondazione Querini Stampalia in Italy, where she chaotically weaved domestic stories about homeless women, squatters and fairy tales with decorative melancholy.

In self-taught artists’ and children’s art the house and interior are one of the most popular motifs next to figures, animals and fantastical beasts. American artists from the 20th century such as William Hawkins, Howard Finster and James Castle paint and draw interiors and buildings whether as backdrops for their puppets, or as illustrations of political and social life in their times. While the homes and buildings are not the central focus of the works, they serve as a tether for more imaginative drawings and paintings.

In the late 19th century Europe, Édouard Vuillard was a prolific painter of interior scenes. His “Interior of the Work-table” (1893), is one of the most honest domestic scenes painted to date. The domestic is emotionally dense, just as Vuillard’s paint is rapid, jam-packed and claustrophobic with its busy color scheme, potpourri of pattern, and figures lurking or holding court.

Somehow the woozy interiors of Edvard Munch and Vincent Van Gogh still relate to the interiors of contemporary artist Mamma Andersson. While Andersson’s interior works are described as “dream-like and expressive”, I find their magic, just as Munch’s and Van Gogh’s, is in their awkwardness. Everything in the interior space is slightly off and brackish giving the work an unforgettable unease. These painters seemingly relieve themselves from their interior studies by having an equal amount of work focused on the exterior, natural landscapes, almost as if to wash off the stain of too much inward focus.

UK-based sculptor Rachel Whiteread has turned the inside out of houses, continually molding and pouring to create sculptures of the quotidian such as bathtubs, closets, bookshelves and entire houses. The resulting installations and objects take on an eerie feeling. A life-sized cement pouring of a home or rooms such as “Ghost” (1990), and “House” (1993) suggest the heavy weight of trauma, trapped emotions, and confinement.

Many female photographers masterfully capture the nuanced mix of intimacy, fear, banality and care that typically inhabit four walls. Sally Mann takes a most intimate, and to some controversial, dive into the home in her photo series of her family. Tina Barney takes a choreographed documentary approach to families of the leisure class which looks either universal or crass depending from what angle you view the work from. Locally, Ann Ploeger takes an expert, color approach and a curious interrogating gaze to the family unit in her portrait series.

A project by architect and artist Jorge Otero-Paios illustrates an unusual and charming take on home. In 2008 he completed an “Olfactory Reconstruction of the Philip Johnson Glass House”. After the National Trust for Historic Preservation took control and cleaned the home for preservation Jorge felt that removing the natural odors associated with this home was disingenuous. His project created a series of three smells based on archival research that reconstruct the 1949, 1959 and 1969 smells of this iconic American house.

Most recently I visited Ann Hamilton’s temporary exhibit habitus in Portland, Oregon. The installation is a meditation on home, threads and community. In true Ann Hamilton fashion there was a precise mix of reading materials, physical materials, historical material, interactive works, sound and community participation. Before the installation she asked for contributions from people, whether poem, writing or illustration of what home meant to them. She curated these and had them printed out for the audience to take away should they choose. These were mostly quotes from other authors, poems, excerpts from architectural drawings, and pictures of interiors.

The stars of habitus were giant hanging hoops with yards of what looked like linen drapes that swung and twisted in the breeze. They also spun from people pulling on bell ropes with soft blue and white striped-sallies fastened to them. They look like billowing skirts a giant with a 20-foot wide waist would wear, where the skirt drapery hangs gracefully 40 feet down. They are in fact made from Tyvek, a plastic used in home construction, and were pulled up at certain points in their construction as if to tempt the viewer to inspect under the skirt. Perhaps another temptation to understand what is under the roof of a house? What is inside that is not available to the public?

Making the bells semi-controllable, where visitors pulled on cords of varying difficulty, was meant to symbolize the town bell which used to have major significance in communities in the past. The bell would signify the time, it would signify the center of the town, and, if one was traveling, hearing the sound would signal you were close to home. At times the pulling of the ropes was useless given the strength of the surrounding winds, begging the question who really is in control when we create safe places for living, mother nature or us?

Two words that rarely go together are homelessness and art. Could these Tyvek skirt-bells also signify the gnarly and urgent problem of homelessness too? Where the city is bubbling up with tarp covered homes for people who have supposedly been given bus tickets to arrive to a friendlier homeless environment? How do we reconcile fancy art work by a renowned artist and local homelessness?

Next to the habitus installation was a Home Shelter Re-Usable Kit designed by Steve Hix, open to explore for the duration of the installation. This “safe place to rest and heal and grow” is a self-sustaining home that can be constructed like a Lego set. While it is not a work of art per say, it is an urgent meditation and project on how to provide housing on the fly for disaster situations such as massive homelessness caused by socio-economic disparity, drug epidemics or environmental catastrophe.

Ask anyone if they would prefer to “go to their studio” or “to the office” versus “work from home” and there will be a resounding wish to have something outside of the home to retreat too. If we scratch the surface of statistics we’ll find that more violence against women, including a staggering death toll, happens quietly and unbeknownst to the public within the home. While we rightfully raged about police brutality where in 2017, 1,147 people were killed by an officer (25% of 1,147 were black), ten years ago, 2,340 deaths were caused by intimate partner violence (70% of these were female). Today three American women are murdered every day by their husband or boyfriend.

Because of the dark clouds resting around home, whether homelessness, domestic violence, terror, dysfunction or general discomfort, is it possible that this era of housing and home that we live in is a hiccup in the evolution of humans? Is it possible we are actually meant to be nomads, and that houses create blocks to growth, creativity and community? We know that four thousand years ago there was a pastoral nomadic culture in Asia that thrived. This was an equestrian group that left behind many objects showing their reverence for animals and nature. Years later we know the Plains Indians in the United States and Canada, who have remarkable cultures, also were migratory, equestrian and held a deep respect for nature. The moment we set lines in the sand, claim property and build houses, something is lost.

Art doesn’t lie, it reflects all of the conscious and subconscious traits of any given time. The home can breed a dystopia of power struggles and a sense of discomfort and ennui on no uncertain terms. Despite our culture’s insistence on domestic bliss, and our obsessions with real estate and home makeovers, we are plagued by how we really feel about being boxed in and domesticated. Homemade in the space of an artist’s studio feels totally wrong, and yet homemade implies made with hands and without the help of outside sources which simultaneously feels right for an artist. Is it possible that the home is a concentrated expression of our culture’s temperature? Our macro-inability to be harmonious with nature, strangers and the universe could be mirrored in our micro-universe that is the home.

Tagged: Ann Hamilton, domestic, domestic violence, Edvard Munch, femme maison, habitus, home, Howard Finster, James Castle, Jorge Otero-Paios, Kiki Smith, Louise Bourgeois, Mamma Andersson, Rachel Whiteread, Vincent Van Gogh, William Hawkins

0 Comments

Would you like to share your thoughts?