Consequently, everything that concerns creativity is invisible, is a purely spiritual substance. And this work, with this invisible substance, is what I call “social sculpture.” This work with invisible substance is my domain, at first, there is nothing to see. Subsequently, when it becomes corporeal it appears initially in the form of a language.

-Joseph Beuys

Olfactory art’s immaterial qualities, you cannot see it, disrupts systems of representation. This silent and borderless focus is a radical reaction to the hyper-retinal, material systems of capitalist exchange. Throughout art history we see examples of artists stripping meaning from systems and materials through rebellious practices and utopian promises. In this essay I will share the parallels between the revolutionary art practices of Kazimir Malevich (1879-1935) and Joseph Beuys (1921-1986), illustrating that the destruction of meaning behind material in their work was an act of defiance that created new ways of considering society and politics. I believe olfactory art is also capable of obliterating the material assumptions of art to create new meanings, all in favor of a more spirited and connected world.

By obliterating material, I mean obliterating the traditional meaning of materials. Beuys and Malevich were insistent on the invisible worlds they addressed with their work: while the fat is material in Beuys’ art, the artwork was not about fat, but the mixture of it with other materials. The resulting alchemy were in his words “social sculptures”: invisible gestures made to shift people’s consciousness. Likewise, Malevich obliterated the traditional material meaning of paintings: he stripped the canvas of meaning by removing any material depictions. In his effort to destroy the “old world” of cultural nostalgia, the meaning of the material painting was destroyed. Similarly, olfactory artworks are not about the fish oil, flower, sweat or urine, but a broader concept beyond the material. It is important the reader consider that the death of an object, or the visual in art, is analogous to creating a new, empty space for contemplation.

Our society values material and tangible objects, therefore artists using invisible, olfactory material are creating a resistance. An exception to this is olfactory artists working in the perfumers’ landscape. These artists are doing an institutional critique of perfumery (e.g. Eau Claire (1997) by Clara Ursitti), and are suitable to another essay dealing with material formulation of olfactory art. In my opinion, an olfactory artwork should not be assessed in reference to its material weight or composition, just as it would be futile to discuss the etching ink quality of Käthe Kollwitz’s Woman with Dead Child (1903).

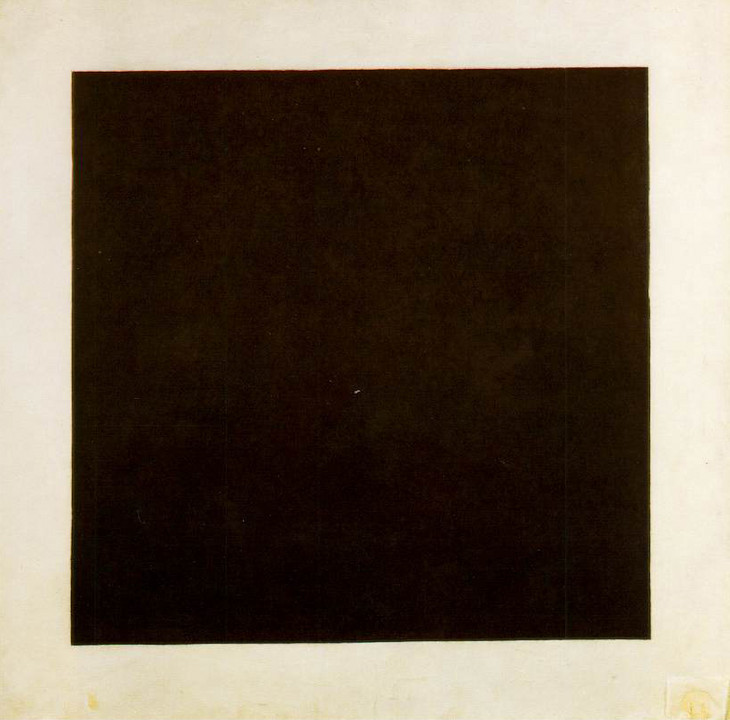

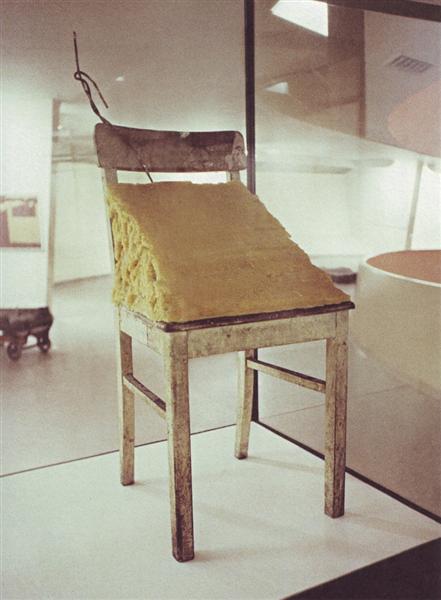

The olfactory medium’s non-linguistic characteristic creates new vehicles for understanding and discussion outside of the gallery, museum, or institutions where the atmosphere takes precedence over the material. For Malevich and Beuys, the material medium also took on a new meaning: for Malevich the strict removal and displacement of material became the spirit of the work, such as his eponymous Black Square (1915) or Suprematist Composition: White on White (1918). For Beuys the physical material became the spiritual node for transference: while there is material in Beuys’ work, it’s the third invisible meaning of the material alchemy, not the actual material, that is its strength as illustrated in works such as Fat Chair (1964, fat and chair), I Like America and America Likes Me (1974, wolf, ambulance, artist, cane, gallery), and the Free International University (1973, students, ideas, teachers) . For artists using the olfactory medium the invisible part of the work, the scent, becomes a radical language. This radical language is separate from a perfumer’s tool kit, where the olfactory is precisely material: artists rely on the atmosphere materials illicit without adherence to the science or systems of mixing olfactory materials.

By using banal, anti-art materials such as honey, urine or cooking spices in the usually “sacred space” of the museum or gallery, the artists I will discuss pivot the audience’s consciousness from the material to the immaterial qualities of the work: the atmosphere of the work becomes more important than the actual material. The borderless and invisible quality of scent are olfactory art’s superpowers. For example, a simple closet space with a lightbulb is transformed with meaning only by the smell of beeswax on the walls of Wolfgang Laib’s, Wax Room (Wohin bist Du gegangen-wohin gehst Du?/Where have you gone-where are you going?), (2013). If the silent olfactory asset of the materials was absent, there would be no artwork – the invisible element of the work becomes paramount.

Sociolinguistic professor Adam Jaworski explains, “Deliberate silence, deliberate negation, is a major way of sustaining the elusive spiritual atmosphere of the abstract work by ruthlessly reducing artistic (“tasteful outer beauty”) to an absolute minimum.” Olfactory artists are operating in the pared down invisible space of scent to give their work meaning. By abandoning the “prison of things,” as the Italian academic Ronato Poggiolo described abstract art doing in the 1950s, by means of silence and negation, the artwork, particularly olfactory art now, becomes free and intense with feeling (Poggiolo 202).

Square: Material Obliteration and Art | Death of the Object

In the year 1913, trying desperately to free art from the dead weight of the real world, I took refuge in the form of the square.

-Kazimir Malvich

In 1915, the year Malevich debuted his first objectless artwork, Black Square, Russia was entrenched in World War I and moving toward the October Revolution of 1917. Hierarchies were being flipped, and the world as people knew it was upended. A Tsarist legacy and economic plan was being destroyed to make way for a market and communist society. Malevich believed that because of the radical disruption in politics and society, art too must be overturned. Out of a sea of ideological art where populist themes and accessible realist styles reigned, he created a daring new language of shapes and forms in his painting, where the radical simplicity of the works challenged all art that had come before. After naming his “new art” Suprematism a few years later he announced, “To the Suprematist the visual phenomena of the objective world are, in themselves, meaningless; the significant thing is feeling.” (Malevich 67)

Malevich’s focus on the absence of material reference was a destructive wish to delete all political and aesthetic orders of his time: the new could only happen with the end of cultural nostalgia. Soviet era-art expert Boris Groys notes ‘(Malevich’s artwork) …announced the death of any cultural nostalgia, of any sentimental attachment to the culture of the past. Black Square was like an open window through which the revolutionary spirits of radical destruction could enter the space of culture and reduce it to ashes.’ (Groys, e-flux).

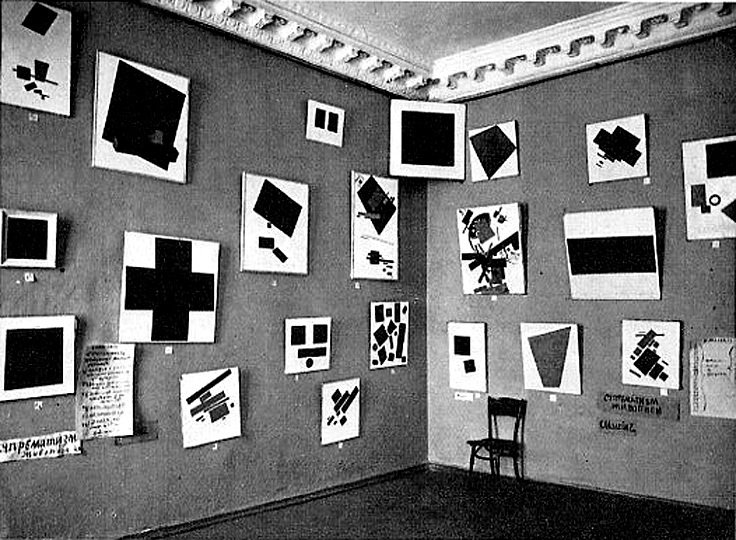

Malevich believed his work to be so spiritual that in 1915, in a show titled The Last Futurist Exhibition of Painting 0:10, in 1915, he debuted his painting Black Square in a way that paralleled the display of Russian religious icons. Malevich placed this artwork in the sacred upper corner of the room (krasnyi), the place where traditionally icons would be placed in the homes of the Orthodox faithful (Mudrak 91). This gesture marked his painting as a new icon of his times, a sacred dark spot. The exhibition in Petrograd, presented by the Dobychina Art Bureau, inaugurated the Suprematist movement, and many historians consider it to be one of the exhibitions that changed the course of art history (Altshuler 173).

Rendering color, and any aspect of utilitarian life, aesthetics, or beauty silent the black painting was independent of aesthetic and social-political conventions of the time. Historian Philip Shaw describes these black paintings as a “preoccupation with the fraught relations between darkness and perception, with the obfuscation of vision as a principle of sublime incomprehension.” (Shaw, Tate)

Malevich and his Suprematist peers including El Lissitzky, Ilya Grigorevich Chashnik and Sergei Yakovlevich Senkin looked continually for non-visual clues to another universe, whether those clues were sound waves, magnetic waves or language experiments. Each invisible clue meant they were closer to the spiritual and radical nature of the unconscious life in this universe. As Malevich describes in his book The Non-Objective World:

“Under Suprematism I understand the supremacy of pure feeling in creative art. To the Suprematist the visual phenomena of the objective world are, in themselves, meaningless; the significant thing is feeling, as such, quite apart from the environment in which it is called forth (Malevich 117).”

Malevich’s profound, objectless perspective inspired generations of artists eager to explore their ideas in ways other than figuration. Artists working with the olfactory take this mission further by exploring feeling silently through scent. Like Malevich removing the meaning of a profoundly sacred space, artists are disrupting the white cube and museum with work whose invisible qualities of the material are the focus. While there is a material aspect to olfactory art, it is subverted for a broader concept of atmosphere and feeling just as Beuys and Malevich used materials. The artists are invested in the immaterial quality of the work, rather than the material: the spirit of the work reigns supreme.

A curious project links Malevich to the perfume world, though not olfactory art. Before he became famous with his radical politics and art, like many artists he sought to support himself with commissions. He designed a perfume bottle for Severny in 1911. While a curious fact, I would caution linking this to broader contemporary olfactory art, which would be akin to artfully linking Jasper Johns and Robert Raushenburg to the jewelry business for the window displays they designed for Tiffany in the 1950s.

Fat: Material Alchemy and Art | Death and Rebirth

The outward appearance of every object I make is the equivalent of some inner aspect of human life.

– Joseph Beuys

Like Malevich who embraced the immaterial by removing meaning behind materials, Joseph Beuys fused philosophy, religion, education, and everyday materials to make a new art focused on the spiritual aspects of human creativity. For Beuys the spiritual was a necessary salve for what he saw as an increasingly rational and uncreative society. His performances and “social sculptures” had a mission to heal and reform post-Nazi Germany. Beuys transformed materials in his art, using an alchemical approach as a way to articulate the spiritual. While Malevich was radically opposed to the politics of Lenin at his time, where his Suprematist art in its non-objective state was a rejection of the imitative-art of the proletariat during the time of Lenin, Beuys was rejecting the strict culture of Germany post World War II which he saw as stifling and unimaginative.

In Beuys’ new art, ceremonies and natural materials reconnected humans to nature, and opposed the rational and efficient society he saw as a threat. Beuys shares a spiritual vision of art similar to Wassily Kandinsky’s, in which art has redemptive and transformative qualities, and in which art is interdisciplinary. Where Kandinsky charted the “nightmare of materialism” to the “kingdom of the abstract” through traditional painting materials and in his book Concerning The Spiritual in Art (1911), Beuys chose to work with materials that were not associated with art, such as his famous sculpture Fat Chair (1963), in which butter and a chair were used to stimulate a discussion about sculpture and culture. Fat Chair is an example of what Beuys considers the “alchemy of life”: a transformational process through which material substance becomes the immaterial (Taylor 31). By using these everyday materials in the context of the gallery, his sculpture caused friction with the audience, forcing them to attest to the invisible or spiritual meaning behind the works, versus an obvious narrative of these objects.

Beuys heralded the 1960s Fluxus movement, which was a reaction to object-oriented art and a rejection of heroic gestures in art, just as Malevich was reacting to and dismantling the objects in art in his time by negating any references to past art in his paintings, and just as today olfactory art seems a reaction to incessant materialism and to “festival art,” as coined by art critic Peter Schjeldahl (Schjeldahl 85). The thread between these three distinct times and movements is a keen awareness of the systems of representation in place, and an effort to move art into a new conversation with audiences. Audiences of olfactory art have no precedence to consider the new work, just as Beuys’ audience had no reference to art using dead hares and wolves, or Malevich’s audience having no reference to solid black square paintings placed in the holy corner of a household. By using materials whose traditional definitions are silenced, a new art emerges.

While Beuys was considered a member of the Fluxus movement, he saw Fluxus’s provocation as insufficient for the transformation of society, a transformation he believed artists must undertake. Therefore Beuys, like his critics, continually aligned his work with other philosophies and movements, such as Arte Povera, or “poor art” as he evolved as an artist. Arte Povera (1967-1972) was a radical Italian art movement where artists used humble, everyday materials in unconventional ways (e.g. Michelangelo Pistoletto’s Venus of the Rags (1967, 1974) or Jannis Kounellis Untitled (12 Horses) (1969).

Beuys expertly blended fact and fiction in the name of art and transformation. Beuys claims to have been resuscitated by Tatar healers in Crimea when he was injured as a soldier during World War II. This trauma influenced Beuys’ entire career and is known in art history as the ‘Tartar Legend’ or ‘Tartar Myth’. Profoundly affected by the crash, the severe trauma, the near-death experience and his rescue, which he perceived as a “rebirth”, Beuys no longer saw himself, other people, or society and materials as a whole in the same way as previously (Ottoman et al).

This experience inspired his interest in Shamanism, a practice in Siberia, Central Asia and the Americas, in which shamans interact with the spirit world in order to heal others and act as spiritual leaders for their tribes. Working as an alchemist, he transformed abject or mundane materials such as butter, animal hair, or blood to create an experience that went beyond the material aspects of his projects. Beuys took the materials the Tatars used to revive him and transformed them in his art, where they came to symbolize rebirth and regeneration.

For his first solo show, in 1965, titled How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare, Beuys walked around the Galerie Schmela in Düsseldorf holding a dead hare. Beuys’ face was covered with gold leaf and honey, and he had attached an iron slab to one of his shoes. Unlike his predecessors working abstractly to explore invisible, spiritual worlds such as Wassily Kandinsky and Hilma af Klimpt, Beuys did not illustrate the immaterial; instead he was relying on alchemy, via his performance, to transform the materials into a spiritual effect for the audience. Each of the materials was symbolically blended to make an invisible statement. For example, the honey represented the ideal society of the bees, which Rudolph Steiner of Theosophy fame promoted as evidenced in his “Nine Lectures on Bees” done in Germany in 1923, and iron, the metal of Mars, represented the principles of strength, masculinity, and a connection to earth.

Just as Beuys blended materials were a way to ignite people’s imagination and reconnect human’s with nature, so too does olfactory art return the audience to experience art in a full-bodied way. Olfactory artists also blend and mix materials so that the essence of the work becomes a third meaning. The material is never the illustration for the work, but the springboard for a more critical aspect of the work: the feeling. For example, by combining the scent of rotting fish to a meticulous display of rhinestones sewn onto fish corpses Lee Bul’s Majestic Splendor (1991-2018) examines the consequence of culture, mass repetitive labor with the artist and museums. The chasm of disconnect between the material and the physical space (the MOMA New York and the Hayward Gallery London) is the essence of the piece.

Air: Material Silence | Death of the Visual

Art no longer cares to serve the state and religion, it no longer wishes to illustrate the history of manners, it wants to have nothing further to do with the object, as such, and believes that it can exist, in and for itself, without “things.”

– Kazimir Malevich

In a time when we are continually asked to define and categorize, the sheer ambiguity and borderless quality of olfaction is radical. Olfactory art is slow, liminal and non-linguistic. There are no canons to guard interpretations of it, it is an open invitation for all to consider and experience, without the weight of criticism or art historical precedent. It could be said that olfactory art is democratic, as it has not been ensconced in an economic system and is open for all to experience. Contemporary olfactory art is defined as, not perfume, but art that uses scent as a medium and is meant to be shared in galleries and museums or as public performances. While there are material aspects of creating and presenting olfactory art, its essential aspect is the invisible, borderless and transcendent nature of scent. Olfactory art gives its audience a nonverbal experience; the visual plays a supporting role and silence is the guide.

While there were some olfactory aspects to the works in Modernist circles, such as the use of abject material in Arte Povera, Fluxus, and Dada, olfactory art has not had a seat at the table of fine art until recently. An opportunity for scent in art and its mysterious, unpredictable nature arose with the increased study of the senses in the 1980s, in particular the work of Canadian anthropologists Constance Classen and David Howes, and in Alain Corbin’s The Foul and Fragrant. While scent was used in these texts and research as evidence for anthropological, feminist, and cultural studies, it also became fodder for the artist’s tool kit.

While olfactory artists may not explicitly call their work spiritual, as Malevich and Beuys did, the use of scent as a way to disrupt an audience carries the heavy weight and history of the spiritual. When it is advantageous for all minds to think alike, such as in a church or temple, the practice of using scent to summon attention is powerful. Since antiquity cultures have utilized the power of scent as a symbol and aid in prayer. Incense was used in ceremonies and temple worship in Babylon, Israel, ancient Greece and Rome, and throughout Asia since the Bronze age. This intense physical and psychological effect of scent on audiences adds another dimension to olfactory art, further emphasizing its radical nature.

As academic and theorist Jim Drobnick put it, “…. given that air is essential to breathing and life, smells inevitably carry ethical concerns and factor into cultural politics. As each inhalation brings in a small portion of the outside world, scents disrupt the traditional distinctions between the environment and bodies, self and other, nature and culture. In these ways, smells create predicaments that interrogate and force a reconsideration of accepted knowledge and aesthetics.” (Drobnick)

Drobnick emphasizes the return to the body with olfactory art, an art that literally inhabits our bodies through the act of smelling. Borders between mind and body, self and other, are erased. The personal is political—our bodies and minds are the center of the olfactory art equation. This corporeal experience in galleries and museums is a reaction to the years of intellectualizing art; our thinking has strayed so far from our bodies that mental intelligence is divorced from bodily intelligence. Luckily, we are swinging back to radical, full-bodied, experiential arts that have incredible powers of persuasion and affect both the emotions and the intellect of their audiences.

In the 1970s, performance artist Adrian Piper began a series of street performances titled Catalysis, one of which included covering herself in a mixture of vinegar, eggs, milk, and cod liver oil; she spent a week traveling through New York’s subways and bookstores in this condition. Piper used the invisible medium of scent to interrogate the boundaries of race, sanity, and the public and private. The word “catalysis” means a chemical reaction in which a catalytic agent remains unchanged. Piper considered her audience’s mute reactions to her and her scent, realizing that despite her noxious, aggressive odor she remained unseen. Like catalytic agents, the audience remained unchanged and outwardly unaffected by her actions. While Piper may have considered her audience as unchanged in order to support her larger thesis of race and feeling invisible as a black woman, I believe that the public likely was affected by her smell, yet there are no socially acceptable ways to show this publicly.

In 1997, Angela Ellsworth performed a similar piece to push the boundaries of engagement and to subvert expectations. Ellsworth soaked a cocktail dress in her own urine, and then she walked around the gallery for the opening of the Actual Odor exhibit (Shiner and Kriskovets 273). While Adrian Piper was performing for the public using extrinsic smells, Ellsworth was using her own taboo bodily smells in an art gallery. In both Ellsworth’s and Piper’s performances, context and the immaterial fuel the efficacy and meaning of the project. There are several artists working with scent today to break taboos about our bodies. Sweat, fear, and bacteria join together in intimate projects by artists such as Anicka Yi and Peter De Cupere. In Anicka Yi’s You Can Call Me F, she took swabs of 100 women and, with the help of a synthetic biologist from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, cultivated the bacteria in a billboard designed to “assault visitors” by asking the question “What does feminism smell like?” Yi won the Hugo Boss Prize in 2016 for her use of olfactory mediums and industrial materials to examine “a bio-politics of the senses.” Using unconventional olfactory materials such as agar and bacteria, she shares with her audience living, scented experiences that challenge conventional ideas on race, gender, and class.

Similarly, artist Peter De Cupere offers a variety of olfactory projects in which he challenges conventional notions of scent using everyday materials. In his works, sweat and other bodily secretions sit next to aesthetic sculptural elements and ask, “why not?” In 2010, De Cupere created a piece titled Sweat, in which he collected the sweat of a troupe of dancers and sprayed it on the wall of a glass-enclosed dance studio. Visitors could smell the sweat through a hole in the glass while the dance performance was played on a nearby video.

Olfactory art is objectless and experiential. The radical resists conventions. Art comes from chaos, not systemic thinking. In olfactory art the visual takes a supporting role and feeling becomes paramount. In a time when the visual eclipses all the other senses, focusing on scent today is radical. As Malevich and Beuys obliterate objects and material, so does olfactory art: you cannot hold it or buy it unless an artist has explicitly created a juice for purchase; it is an experience. There’s no doubt that olfactory art, by exploring the invisible, gains prominence in a time when reality has become unpalatable.

We have not set up criteria to judge olfactory works of art aesthetically, though there are patterns emerging concerning the types of olfactory art. There are works that, while they are enhanced by a scent, do not have scent as their central principle, such as Ernesto Neto’s Just like drops of time, nothing (2002). Neto’s piece, which challenges traditional notions of art spectatorship, uses herbs and spices to enhance a series of long, stalactite-like sculptures. This piece is about challenging traditional notions of audiences experiencing artwork. In conceptual works by other artists, scent is suggested without any actual scented material, such as Boris Raux’s The Sprint (2008). In this work Raux packs a hallway with upside down deodorant spray cans; the visual implies that sprinting down this hallway would emit a cacophony of scent. The sprint never occurs, though the visual documents the concept. There are also the “actual juice works,” in which an artist creates a scent, usually from abject material or even from the artist’s own person. These olfactory art projects critique the institution of perfume and its mythical power. One example is Lisa Kirk’s Revolution (2008), for which she bottled “tear gas, blood, urine, smoke, burned rubber and body odor,” and presented it at MOMA PS1, then sold at perfume shops. Lastly, there are works that neither make nor present smells, but observe and map them, such as Kate McLean’s various Smellmaps (2012).

Regardless of the artist’s intention, in each olfactory art category the ultimate translation of the work resides in its immaterial and experiential components. In other words, the translation is the invisible experience of the audience, and where its power as a work of art lies: in the quiet immaterial zone of the audience’s subconscious. While scent is physically material, the feelings it provokes are not, and scent’s superpower in the arts lies precisely in its borderless qualities. The immaterial is the spiritual dimension of the work of art, therefore its radical nature.

Because we have a limited vocabulary for describing scent and lack a settled classification system for odors, olfactory art projects to date have eluded rigorous critical analysis. There is no institutional place for olfactory art, which makes it a radical medium invalidating traditional nodes of art critique. This is also why the scent medium is the best medium for exploring the spiritual, immaterial aspects of the personal and the political: the borderless, silent, and illogical space of scent opposes today’s excessive, loud, and aggressively material world view. Scent’s immaterial action also serves as a renewed connection to our bodies through the act of breathing. The “enveloping presences” of olfactory artworks, as described by Jim Drobnick, “stem from a holistic viewpoint in which art can provide a haven for mending the fracture between the mind and body” (Drobnick 15). Just like the ceremonies in which Beuys attempted to use natural materials to heal the minds and bodies of his ailing society, so to do olfactory artworks shift audience’s perspectives with their invisible presence.

Olfactory art disrupts systems of representation. Where previous artists explored the abstract with terms such as Neoplasticism, always making thought forms visible, olfactory art’s effect exists invisibly. Just like Malevich’s removal of material and Beuys’s transformation of material, the immaterial aspects of olfactory artworks supersede the physical spaces they occupy. The silence of olfactory artworks makes them a powerful force reacting to the politics of the art world and of general consumption. What mid-century Italian critic Renato Poggioli wrote about the avant-garde still applies to olfactory art today: silence “transcends the limits not only of reality but those of art itself, to the point of annihilating art in attempting to realize its deepest essence” (Poggioli 201). While the art world in 2020 shouts loudly for attention from patrons and audience, olfactory artworks sit, silent and powerful. This new medium provides artists with avenues for exploring tolerance, slowing down, returning to our bodies and working in a nonverbal space. Such explorations are desperately needed in the larger world to bridge connections with our bodies rather than make intellectual barriers amongst ourselves and against our natures. Unlike visual artists who translated the essence of the spirit into visual symbols and systems, olfactory artists rely on the invisible to deepen our experience with our times. Olfactory artworks are powerful feats of alchemy which in silence require our utmost attention.

If Frank Stella’s all-black paintings were the “death blow to academic gesture painting,” as noted in 1959 by critic Irving Sandler (Larson 388), then could silent and objectless olfactory art be the death blow to the saturated yet empty vessel that is the art world today? The quiet, slow, spiritual space of the olfactory is radical because it opposes the logical and the rational: there is no story, there is no beginning, and there is no end. Freeing our minds from the storm of our fast-paced, technologically linked lives is essential today, and olfactory art is a vehicle for this meditation and mediation. The act of breaking conventions is political. The future of art may not need the museum or gallery, but we will always need to breathe.

Works Cited

Altshuler, Bruce. Salon to Biennial: Exhibitions that Made Art History, Volume 1: 1863-1959. Phaidon Press, 2008.

Beuys, Joseph, Cahiers du Musée National d’art Moderne, no. 4. Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, 1980.

Joseph Beuys: Transformer, video recording, Mystic Fire, 1998.

Douglas, Charlotte. “Beyond Reason: Malevich, Matiushin, and Other Circles.” The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890-1985, edited by Maurice Tuchman, Abbeville Press, 1986, pp. 185-199.

Drobnick, Jim. “The Olfactory Turn in Visual Art.” Roots and Routes: Research on Visual Cultures. www.roots-routes.org/the-olfactory-turn-in-visual-art-by-jim-drobnick/

“Reveries, Assaults and Evaporating Presences: Olfactory Dimensions in Contemporary Art.” Senses: The Concordia Sensoria Research Team (CONSERT). Concordia University. www.david-howes.com/senses/Drobnick.htm

Eliade, Mircea. Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy. Translated Willard Trask, Pantheon, 1964.

Groys, Boris. Becoming Revolutionary: On Kazimir Malevich. (e-flux, Journal 47, September 2013) accessed April 2020, https://www.e-flux.com/journal/47/60047/becoming-revolutionary-on-kazimir-malevich/.

Larson, Kay. Where the Heart Beats: John Cage, Zen Buddhism, and the Inner Life of Artists. Penguin Books, 2013.

Malevich, Kazimir. The Non-Objective World. Translated by Howard Dearstyne. Paul Theobald and Company, 1959.

Malevich, Kazimir. The Non-Objective World: The Manifesto of Suprematism. Mineola: Dover Publications, 2003.

Mudrak, Myroslava M. “Kazimir Malevich, Symbolism, and Ecclesiastic Orthodoxy.” Modernism and the Spiritual in Russian Art: New Perspectives. Edited by Louise Hardiman and Nicola Kozicharow, Open Book Publishers, 2017, 91-113. books.openedition.org/obp/ 4648

Ottomann, Stollwerck, Maier, Gatty, Muehlberger. “Joseph Beuys: Trauma and Catharsis”. (BMJ Journals, Medical Humanities) accessed April 2020, https://mh.bmj.com/content/36/2/93.long.

Poggioli, Renato. The Theory of the Avant-Garde. Harper & Row, 1971.

Schjeldahl, Peter. “Festivalism.” The New Yorker, July 5, 1999.

Shaw, Philip https://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/the-sublime/philip-shaw-kasimir-malevichs-black-square-r1141459#fn_1_2

Taylor, Mark C. Refiguring the Spiritual: Beuys, Barney, Turrell, Goldsworthy, Columbia University Press, Mar 27, 2012.

Tishler, Jennifer R. Russian 15: Russian Art of the Avant-Garde. Dartmouth University, September 2002. https://www.dartmouth.edu/~russ15/russia_PI/avant_garde.html. Accessed August 27, 2019.

Shiner, Larry and Kriskovets, Yulia. “The Aesthetics of Smelly Art”, The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Vol. 65 No. 3, Wiley-Blackwell on behalf of the American Society for Aesthetics, Summer 2007. doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-594X.2007.00258.x. Accessed April 19, 2019.

Artworks Cited

Beuys, Joseph. Stuhl mit Fett. 1963, Düsseldorf Academy of Art (till 1986)

How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare. 1965, performance at Galerie Schmela in Düsseldorf

Bul, Lee Majestic Splendor (1991-2018)

De Cupere, Peter. Sweat. 2011, performance with Troubleyn/Jan Fabre, Belgium

Ellsworth, Angela. Actual Odor. 1997, performance at Arizona State University Art Museum

Kollwitz, Kathe, Woman with Dead Child, 1903

Kirk, Lisa. Revolution. 2008, displayed at MoMA PS 1, perfume available commercially

Maclean, Kate. Smellmaps, Glasgow. 2012, Glasgow Science Center

Malevich, Kazimir. Black Square. 1915, The State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Neto, Ernesto. Just like drops of time, nothing. 2002, Art Gallery of New South Wales

Piper, Adrian. Catalysis. 1970, performance, New York City

Raux, Boris. The Sprint. 2008, collection of the artist

FEAR of smell — the smell of FEAR. 2006, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Visual Arts Center

Yi, Anicka. You Can Call Me F. 2015, The Kitchen, New York

Tagged: Actual Odor, Adrian Piper, Angela Ellsworth, Anicka Yi, art history, Black Square, Fat Chair, Joseph Beuys, Kate MacLean, Kazimir Malevich, Malevich, olfactory art, Peter Decupere, political, Rudolph Steiner, spiritual, spirituality in art, Suprematism

0 Comments

Would you like to share your thoughts?